Turkish citizens are poised to vote in the most pivotal national contest in a generation: On May 14, they will decide whether to re-elect President Recep Tayyip Erdogan or replace him with opposition candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu. Erdogan has presided over twin economic and security crises, even as he has consolidated power and grown increasingly authoritarian. Kilicdaroglu’s victory would represent a fresh start and an opportunity to improve Turkey’s relations with the West, but his presidency would face major constraints in dealing with the country’s ills, which have become endemic and multifaceted. While Turkey offers long-term opportunities for market growth in key sectors—especially textiles, mining, energy, agriculture, and tourism—investors can anticipate that its crises will deepen, even if the country attempts to recover from populist measures and tackle deeper structural reforms.

This might have been a celebratory moment for Turkey, as it approaches its 100th anniversary as a republic in October. Instead, the country finds itself plagued with sources of instability. Erdogan’s failure to mitigate or respond quickly and meaningfully to the February 6 earthquake, which killed at least 50,000, dramatically exposed a broader set of fault lines related to government mismanagement, military adventurism, and opportunistic foreign policy. As a result, the vote is seen by many Turks as a referendum on Erdogan and his more than 20 years in power.

Criticisms of Erdogan long predate his government’s failures surrounding the earthquake. Turkey’s inflation rate reached 85 percent in October 2022 and remains firmly in the double digits. Unemployment is rising and purchasing power eroding; in April 2023, the Turkish lira hit a record low, at 19.4 to the US dollar, due to unorthodox monetary policies and a gaping current account imbalance. The central bank has nearly exhausted its foreign exchange reserves, and the government has strained its relationships with the IMF and other international lenders. To prop up his political support, Erdogan has lowered the retirement age, raised the minimum wage, and cut interest rates, while also attempting to stabilize the lira through currency swaps with Gulf states. These short-term measures are unsustainable and counterproductive, and they portend a significant economic hangover.

Meanwhile, debates continue to rage over how to manage various components of Turkey’s national security crises, specifically those related to refugees, conflict with the Kurds, and relations with NATO and the EU. Turkey has attracted 3.6 million refugees fleeing war in Syria, with sizable numbers also from Ukraine, Afghanistan, Iran, and East Africa, stretching the country’s resources, creating vulnerabilities to terrorist activity, and leading to widespread public hostility and resentment. Despite refugees providing a cheap source of labor, political leaders across the spectrum have advocated for their repatriation on both economic and security grounds. At the same time, the Turkish military has escalated its conflict with Kurdish groups, while attempting to create strategic depth along the Turkey-Syria border. Turkey has blocked Sweden’s bid to join NATO, ostensibly due to Sweden’s acceptance of Kurdish dissidents and asylum seekers, heightening resentment within the broader alliance. NATO and EU states also bristle at Erdogan’s national-interests-based relations with Russia and China, as well as Turkey’s realpolitik approach to diplomatic and military engagement in Pakistan, Somalia, Libya, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Gulf. An Erdogan victory would almost certainly arrest further EU accession talks, which have stalled due to Turkey’s democratic backsliding and human rights record, as well as the contentious debate with Brussels over refugee flows, among other irritants.

If Erdogan remains in power, Turkey’s economic and national security crises are expected to persist, though this trajectory is not preordained. After he gained prominence as mayor of Istanbul in 1994 on promises to root out state corruption, and for the first decade of his national leadership, Erdogan achieved notable accomplishments: GDP per capita rose dramatically, infant mortality fell, and the economy diversified and grew with the rise of the “Anatolian tigers.” Erdogan also succeeded where his predecessors had failed in bringing the military under greater civilian control. His initial successes rested on a commitment to delivering public services and defending the interests of rural, religious, and impoverished Turks that had been largely ignored by traditional elites. He also made seemingly genuine efforts to expand Kurdish rights and bring about a negotiated settlement of the Kurdish conflict.

In more recent years, Erdogan has used his growing authority to gain control over the media and parliament, reduce judicial independence, and silence those who speak out against him, including through disappearances. Compounding widespread anger at the government’s earthquake response, Erdogan’s ban on Twitter and imprisoning of those who criticize his administration have further eroded his popular support, even among steadfast loyalists from his religiously pious, traditionalist base. Preliminary polling suggests that he is—for the first time in his political career—at real risk of losing an election, despite his influence over the electoral administration and national media outlets. Many observers project Erdogan’s defeat would trigger claims of fraud and lead to unrest throughout the country.

A Kilicdaroglu presidency, however, is hardly a ready-made solution. Representing a six-party coalition, Kilicdaroglu is a serious, 74-year-old accountant and former civil servant who has led the center-left Republican People’s Party since 2010, proving more steely than anticipated and defying expectations that he would be a mere temporary occupant of the role. His ability to effectively govern, however, is totally untested and open to question. Kilicdaroglu and his coalition partners have little in common, other than their shared disdain for Erdogan and a determination to oust the current president, and they have not built a coherent agenda for improving Turkey’s economy, resolving the refugee questions, or managing the conflict with the Kurds. Once in power, Kilicdaroglu almost certainly will find himself stymied by conflicting mandates, as well as undermined by the legacy patronage structures established by Erdogan and his allies. Nonetheless, he would enjoy a honeymoon period with the West, with export-oriented businesses and urban voters, and with elements of the national security apparatus that have silently resented Erdogan’s purges following a failed 2016 coup attempt that was supported by a faction of Turkey’s armed forces. One of the biggest questions facing a potential Kilicdaroglu administration is whether it could revive and implement the kind of policies that first made Erdogan a popular national figure, without resorting to authoritarian excesses.

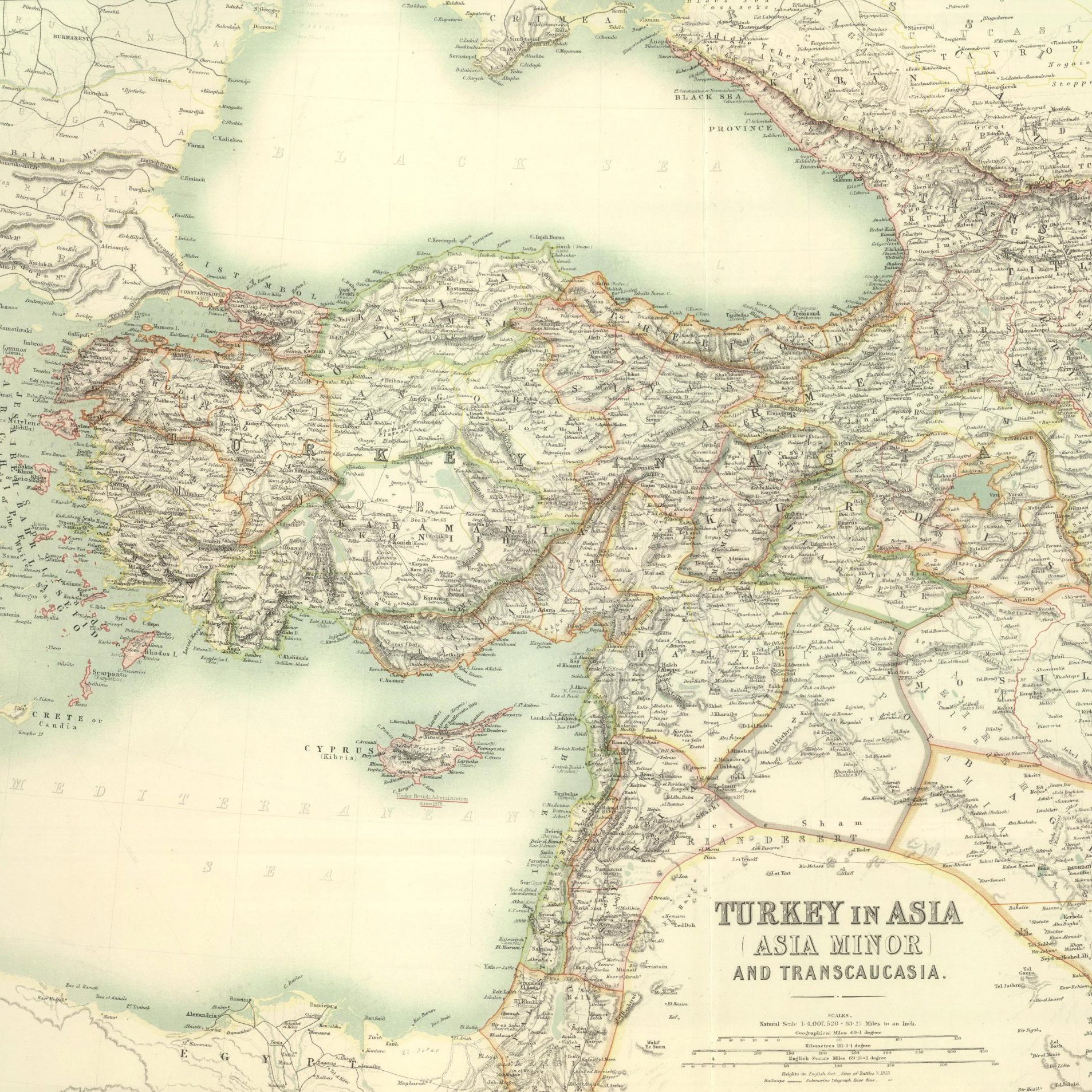

Turkey’s election will have international implications, given its geographic location and geopolitical importance. The country is a bridge between East and West in both cultural and commercial terms, with leading roles in multinational organizations spanning the North Atlantic, Europe, the Middle East, Turkic nations, and the Islamic world. It controls access to the Black Sea from the Mediterranean, and sits at the intersection of critical infrastructure grids, making it a conduit for both people and goods. Turkey hosts US and NATO armed forces with missions that range from combat support to missile defense and strategic deterrence. It is also the only major NATO member to maintain normalized communication channels with Russia, while supporting Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as mediating between Moscow and Kyiv in the UN-brokered grain export deal. Its hospitality toward Russian capital and citizens, flows of which dramatically increased after February 2022, has become an economic boon for Erdogan, though one which Kilicdaroglu could be under pressure to redress. Turkey maintains cordial ties with China—an increasingly important commercial partner for Ankara that has provided sizable direct lending to the Turkish government; in turn, Erdogan has been conciliatory towards Beijing regarding the condition of Turkic Uighurs in Xinjiang.

For investors, Erdogan’s concentration of political power and Turkey’s economic malaise warrant comprehensive risk assessments, though not necessarily wholesale avoidance of the country. While macroeconomic conditions will likely continue to trend negatively in the near term, the country’s next president will have political space to embark on policy adjustments that could have an important signaling effect for the market. Turkey’s frayed reputation with Western countries will be partially mended by its likely approval of Sweden’s NATO bid, expected during the Alliance’s summit in June. At the same time, Turkey’s strategic location, natural resources, young population (relative to European norms), and multi-vector foreign policy will enable its next presidential administration to attract a wide range of businesses that seek to maintain simultaneous commercial contacts with Russia, China, the Middle East, and the West. Regardless of the outcome of the presidential election, amid increasingly hostile competition between global powers, Turkey will remain pivotal in the international system. After almost a century as a republic, it is too confident to stridently shun, overly embrace, or willfully ignore.

Jay Truesdale is CEO of Veracity Worldwide. David Stevens, who holds a PhD from Columbia University in Turkish politics, is Veracity’s managing director responsible for research and analysis. David Alm serves as Veracity’s editor.